Example of a game without a value

In game theory, and in particular the study of zero-sum continuous games, it is commonly assumed that a game has a minimax value. This is the expected value to one of the players when both play a perfect strategy (which is to choose from a particular PDF).

This article gives an example of a zero sum game that has no value. It is due to Sion and Wolfe.[1]

Zero sum games with a finite number of pure strategies are known to have a minimax value (originally proved by John von Neumann) but this is not necessarily the case if the game has an infinite set of strategies. There follows a simple example of a game with no minimax value.

The existence of such zero-sum games is interesting because many of the results of game theory become inapplicable if there is no minimax value.

Contents |

The game

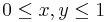

Players I and II choose numbers  and

and  respectively, with

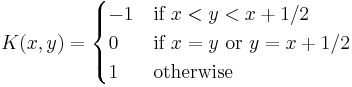

respectively, with  ; the payoff to I is

; the payoff to I is

(i.e. player II pays  to player I;the game is zero-sum). Sometimes player I is referred to as the maximizing player and player II the minimizing player.

to player I;the game is zero-sum). Sometimes player I is referred to as the maximizing player and player II the minimizing player.

If  is interpreted as a point on the unit square, the figure shows the payoff to player I. Now suppose that player I adopts a mixed strategy: choosing a number from probability density function (pdf)

is interpreted as a point on the unit square, the figure shows the payoff to player I. Now suppose that player I adopts a mixed strategy: choosing a number from probability density function (pdf)  ; player II chooses from

; player II chooses from  . Player I seeks to maximize the payoff, player II to minimize the payoff. Note that each player is aware of the other's objective.

. Player I seeks to maximize the payoff, player II to minimize the payoff. Note that each player is aware of the other's objective.

Interpretation

The game is equivalent to a continuous Colonel Blotto game. Player I must assign a force x to the attack of one of two mountain passes, and 1-x to the other. Player II must assign a force y to defend the first pass and 1-y to the other, at which is also located an extra defensive force of strength  . A player receives from the other a payment of 1 at each pass if his force there exceeds his opponent's, and nothing if they are equal value there (from Sion and Wolfe).

. A player receives from the other a payment of 1 at each pass if his force there exceeds his opponent's, and nothing if they are equal value there (from Sion and Wolfe).

Game value

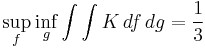

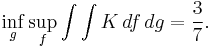

Sion and Wolfe show that

but

These are the maximal and minimal expectations of the game's value of player I and II respectively.

The  and

and  respectively take the supremum and infimum over pdf's on the unit interval (actually Probability Borel measures). These represent player I and player II's (mixed) strategies. Thus, player I can assure himself of a payoff of at least

respectively take the supremum and infimum over pdf's on the unit interval (actually Probability Borel measures). These represent player I and player II's (mixed) strategies. Thus, player I can assure himself of a payoff of at least  if he knows player II's strategy; and player II can hold the payoff down to

if he knows player II's strategy; and player II can hold the payoff down to  if he knows player I's strategy.

if he knows player I's strategy.

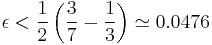

There is clearly no epsilon equilibrium for sufficiently small  , specifically, if

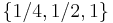

, specifically, if  . Dasgupta and Maskin[2] assert that the game values are achieved if player I puts probability weight only on the set

. Dasgupta and Maskin[2] assert that the game values are achieved if player I puts probability weight only on the set  and player II puts weight only on

and player II puts weight only on  .

.

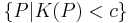

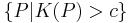

Glicksberg's theorem shows that any zero-sum game with upper or lower semicontinuous payoff function has a value (in this context, an upper (lower) semicontinuous function K is one in which the set  (resp

(resp  ) is open for any real c).

) is open for any real c).

Observe that the payoff function of Sion and Wolfe's example is clearly not semicontinuous. However, it may be made so by changing the value of K(x,x) and K(x,x+1/2) [ie the payoff along the two discontinuities] to either +1 or -1, making the payoff upper or lower semicontinuous respectively. If this is done, the game then has a value.

Generalizations

Subsequent work by Heuer [3] discusses a class of games in which the unit square is divided into three regions, the payoff function being constant in each of the regions.

References

- ^ M. Sion, P. Wolfe (1957). "On a game with no value". The Annals of Mathematical Studies 39: 299–306.

- ^ P. Dasgupta and E. Maskin (1986). "The Existence of Equilibrium in Discontinuous Economic Games, I: Theory". Review of Economic Studies 53 (1): 1–26. doi:10.2307/2297588. JSTOR 2297588.

- ^ G. A. Heuer (2001). "Three-part partition games on rectangles". Theoretical Computer Science 259: 639–661. doi:10.1016/S0304-3975(00)00404-7.